What most people have forgotten about the Electoral College (Pt 2)

The Harris vs Trump edition

It’s July of 2024. The Democratic Party suddenly finds itself improvising a solution to a challenge that parallels what the Framers of our Constitution struggled with in July, of 1787: how do you pick a president?

The modern Democratic Party’s version of the problem is this: how do you pick a new candidate when your presumptive nominee has suddenly withdrawn and you have only four weeks to go before your nominating convention?

The eighteenth-century version of the problem was this: how do you pick a president when there are no political parties, no candidates, and no communications infrastructure to conduct a national campaign?

All signs point to the Democrats solving their current challenge faster and with more success than the Framers solved theirs.

The Framers’ solution was a system that was never fully implemented, although it evolved into our current Electoral College. From the start, it came with a Plan B known as a “contingent election” that still sits inside the Constitution as a bit of unexploded ordinance lurking behind every close presidential contest. Four years ago, Trump aimed at—and came very near to—setting off a contingent election in his scheme to overturn his loss. His campaign is prepared to do it again in 2024.

Before diving into that, however, a few words about the challenge the Democrats face in the wake of Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw from the race.

For the Democrats this week, an obvious, clean solution is rapidly falling into place. The party is quickly converging around nominating Vice President Kamala Harris. It’s coming together faster than most would have predicted. Many stars in the party—too many to list here—have already endorsed Harris; they include Bill and Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, Jamie Raskin, Adam Schiff, Elizabeth Warren, Jim Clyburn, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Gavin Newsom, as well as all 50 state party chairs, and of course, President Joe Biden. A growing roster of state delegations have announced their intention to support Harris at the convention. As of this writing Harris has the endorsement of 42 of 47 Dem Senators, 181 of 212 Dem Reps, and 19 of 23 Dem Governors.

Biden’s withdrawal announcement triggered not just a wave of endorsements, but also a surge of donations—both small dollar amounts given through ActBlue ($81 million in the first 24 hours) and a renewed wave big-dollar donations from Hollywood and Silicon Valley (Future Forward PAC received $150 million in new contributions in the first day since Biden dropped out.)

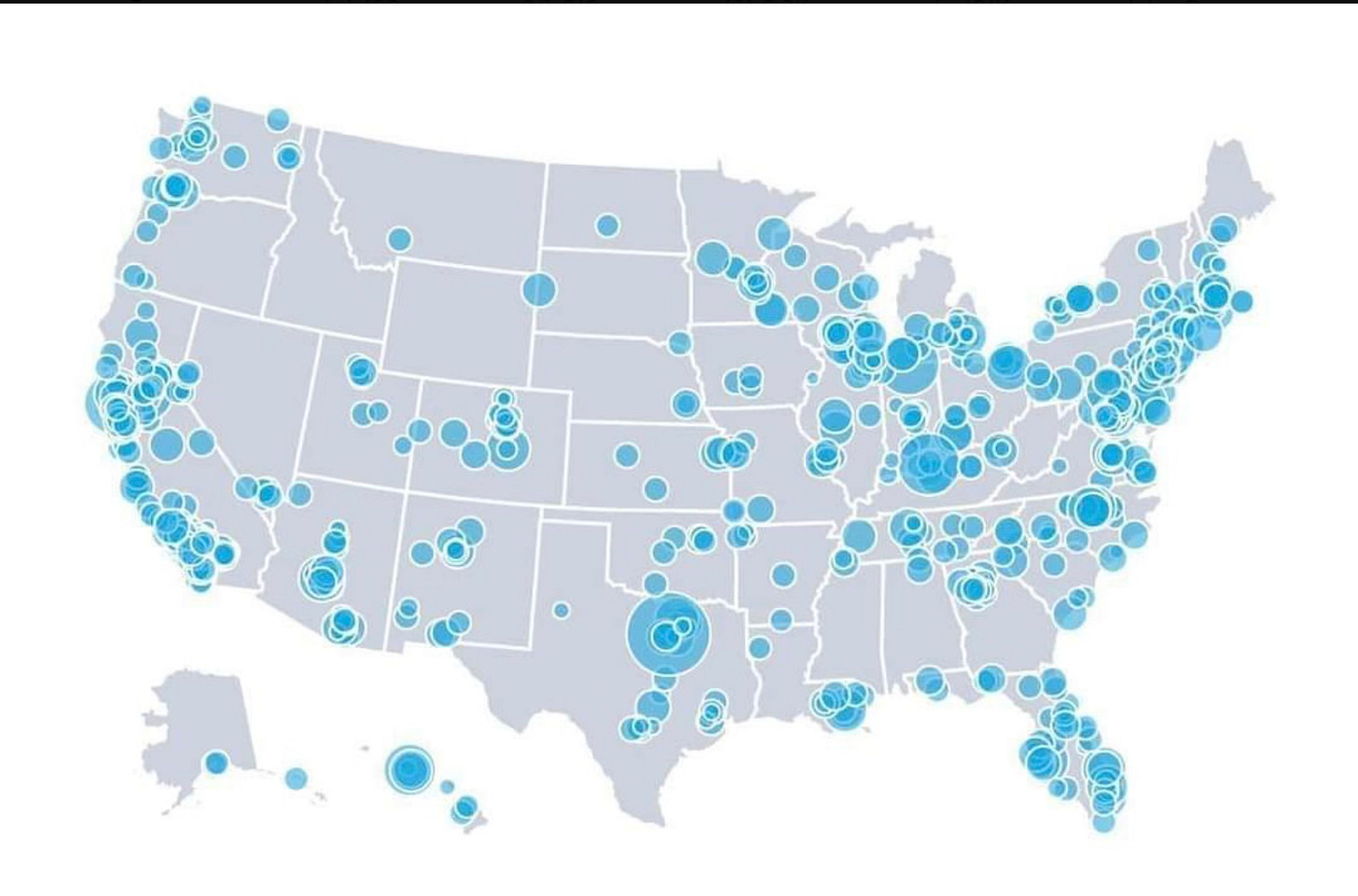

ActBlue released a map showing where donations were coming from, indicating strong support for Harris in swing states as well as reliably blue states

Despite the surging Kamalamentum, some of the most prominent voices in the party—notably former President Obama, Majority Leader Schumer, and Minority Leader Jeffries*—have, as of this writing, withheld their endorsements. They are calling, instead, for the party to devise an “open and fair” process in which Harris would compete with other potential candidates for the nomination. This lack of endorsement likely does not signal opposition or even hesitation. It may simply be a tactical maneuver to manage the process in a way that creates opportunities for Harris to shine in reintroducing herself to the voting public.

[EDIT: Both Leader Schumer and Leader Jeffreys endorsed on Tuesday morning]

What’s unclear as of this writing, however, is whether there are any potential Democrats who will care to step forward to compete with the Kamala Harris juggernaut. It may well be that Vice President Harris has already cleared the field of all potential challengers. At this rate, by tomorrow, it may all be a done deal.

[EDIT: The deal was sealed tonight, as Harris won more than enough convention delegates to assure her nomination.]

By contrast, the Framers efforts to devise a framework for presidential elections were muddy from the start. Although it never operated as planned, we have some strong clues of their intent in Madison’s Notes on the Debates, and in Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 68. We can see the shadows of a plan that was never fully realized and which has been largely forgotten.

The key element that was lost as the original scheme evolved into our current system is that electors weren’t originally expected to vote for designated candidates as they do today, but were instead tasked with the job of scouting and screening potential candidates for the presidency.

Electors: the original nominating convention

Of all the offices created in our constitutional system, electors are the most ephemeral. House members serve for two years, presidents for four, senators for six, judges for a lifetime, but electors serve barely an hour. They meet. They vote. They sign. And then they go home. In the original plan, however, they had a more substantial role.

Unlike today, when a slate of partisan electors arrive at their meetings already pledged and committed to a specific candidate, the original plan called for unaligned, non-partisan electors to do the work of discovering and presenting the most worthy candidates. In the absence of political parties, primaries, or conventions, the electors had to also be the nominators. The closest modern parallel to their job description might be a corporate executive search committee that also the power to hire a new CEO.

In itself, combining nominators and electors into one body would have been problematic enough. But the problems were multiplied by thirteen. By design, the electors never convened together as a “college.” (The term “Electoral College” doesn’t even appear in the Constitution). Instead, they were to meet separately in their respective states. They would have functioned as thirteen independent executive search committees. It’s almost as though the system was set up to prevent the electors from actually electing a president. The odds that thirteen independent committees might converge on a single majority candidate were between slim and fuggedaboudit.

There’s evidence that the Framers were fullyu aware of that. Why, then, did they set it up this way? In creating a strong executive, they wanted to insure that the office remained independent. So, they went overboard to guard against corruption and entanglements. Among the entanglements the Framers feared most were cabals, mob pressure, and foreign influence. The use of independent ad hoc panels of electors was meant as a shield against all of that. As Alexander Hamilton put it:

No senator, representative, or other person holding a place of trust or profit under the United States, can be of the numbers of the electors…Their transient existence, and their detached situation… afford a satisfactory prospect of their continuing so, to the conclusion of it…It was also peculiarly desirable to afford as little opportunity as possible to tumult and disorder… And as the electors, chosen in each State, are to assemble and vote in the State in which they are chosen, this detached and divided situation will expose them much less to heats and ferments, which might be communicated from them to the people, than if they were all to be convened at one time, in one place.

In the final Convention debates over the proposal for electors, Charles Pinkney of South Carolina noted this obvious drawback of the scheme, “The Electors will be strangers to the several candidates and of course unable to decide on their comparative merits.”

And so, the proposal for electors came with a Plan B.

Look at the language of the draft article:

“…if no person have a majority, then from the five highest on the list, the Senate shall choose by ballot the President.”

“Five”? Instructing the Senate to narrow the choice to the top five indicates strongly that the Framers anticipated a large number of names to come in from the electors who would only rarely manage to agree on a majority winner. Col. George Mason of Virginia estimated that “nineteen times in twenty the President would be chosen by the Senate.” That would amount to a 95% failure rate.

It’s clear that the electors were likely to get no farther than producing a list of nominees for the Senate to pick from. (Note: While holding contingent elections in the Senate was in the original draft, the Convention quickly changed that to the House of Representatives. They argued that if the Senate picked the president, it would conflict with their ability to try impeachments.)

Why don’t we have contingent elections anymore?

It’s fair to ask why, if contingent elections for president were expected to be the norm, have we only had two of them in our entire history, and none at all in the past two centuries?

Even at the time of the convention, Abraham Baldwin of Georgia recognized that contingent elections would soon fade away. As Baldwin noted:

“The increasing intercourse among the people of the States, would render important characters less & less unknown; and the Senate would consequently be less & less likely to have the eventual appointment thrown into their hands.”

Beyond that, a list of additional historical changes helped hold contingent elections at bay, including the rise of parties, the advent of presidential campaigns, the 12th Amendment, the technical advancement of communication and transportation, and the tactic soon adopted by states of committing their electors to vote as a block. Since 1824, the electors have always managed to deliver a majority.

While the likelihood of contingent elections has faded, the provision to hold them still remains in the Constitution, enduring as a tempting target for anyone seeking to manipulate the system. Make that any Republican seeking to manipulate the system. As things stand, contingent elections skew even more toward Republicans than does the Electoral College itself.

The enduring threat of contingent elections

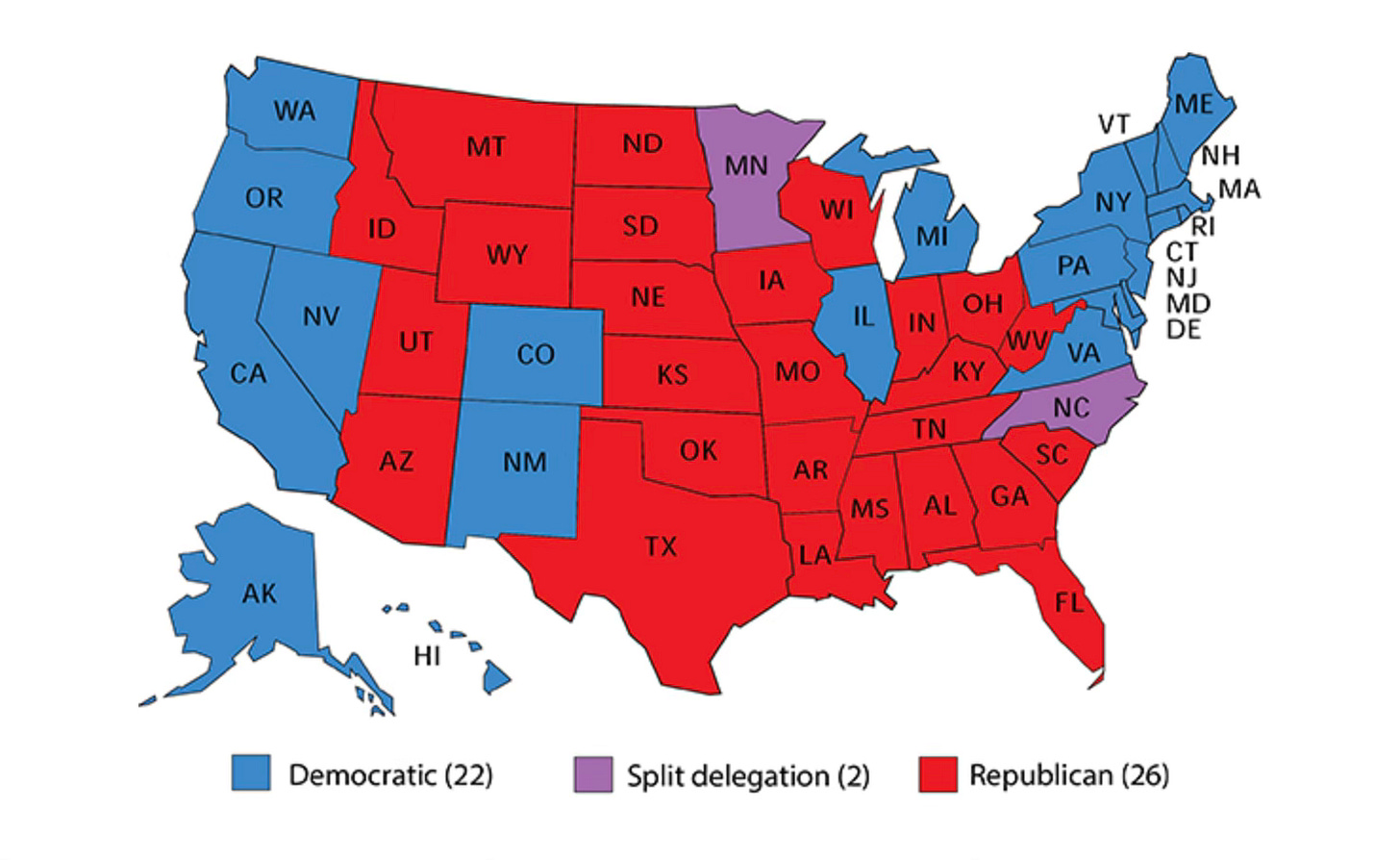

If no candidate for president wins a majority of electoral votes and the contest moves to the House of Representatives, each state gets one vote. This was intended as a concession to the smaller states, but as it stands now, it’s pretty much a guaranteed win for the Republican candidate. Even if Democrats manage to regain a majority of seats in the House this November, they are unlikely to control a majority of state delegations. In the current Congress, for example, the division is 26 Republican states to 22 Democratic, with two state delegations evenly split. If the Trump plot had managed to send the decision to the House, he would have won 26 to 22.

Donald Trump’s “fake elector” plan to overturn the 2020 election rested on triggering a contingent election and his plans for 2024 target the same vulnerability. The possibility of preventing an electoral majority explains the active support that MAGA donors and Trump himself are lavishing on the third-party candidacy of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

The continued peril of contingent elections is an enduring legacy of a forgotten flaw in the original design of our Framers, who, in the absence of official candidates and campaigns anticipated that presidential electors would usually fail to reach agreement on a majority candidate. While we’ve managed to successfully route around that flaw since 1824, we haven’t eliminated it. And when a campaign, such as Donald Trump’s is determined to win by any means available, that flaw emerges as an active, available target.

It’s why I always tell people in red states to work on flipping their state blue if they want lasting change.

People focus way too much on federal elections.

Very informative and insightful. Thanks for taking it on!