What most of us have forgotten about the Electoral College (Pt. 1)

Most Americans want to abolish it. But few know its origin story.

The Electoral College is a mess that has never functioned as it was intended to by the people who dreamed it up. In fact, the role of electors has moved so far from its original design that we’ve all but forgotten how it was expected to work.

In 2016, however, we came close to remembering:

When Hillary Clinton won the vote of the people (by a margin of 2,868,326) but lost the vote of the electors (by a margin of 77) some activists pleaded with electors to ignore the wishes of their state’s voters and honor the national popular vote.

Despite naming their efforts after the principal author of The Federalist, what the “Hamilton Electors” proposed didn’t actually reflect Hamilton’s views. Nor did it correspond to any other historical reality except for the occasional and sporadic appearance of rogue electors, whose departure from their instructions has earned them the title, “unfaithful electors.”

Our current Electoral College is a vestige of a design that was crafted for an era in which the presidential campaign had not yet been invented, wasn’t needed, and would have been impossible to conduct. It was designed to work without political parties and without mass media. The outline of the system that the Framers thought they were creating is preserved within the Notes of Debates at the Federal Convention, as recorded by James Madison, and in Alexander Hamilton’s essay Federalist 68.

It’s a system that was never fully realized before it evolved into the unpopular distortion of democratic principles that we are stuck with today.

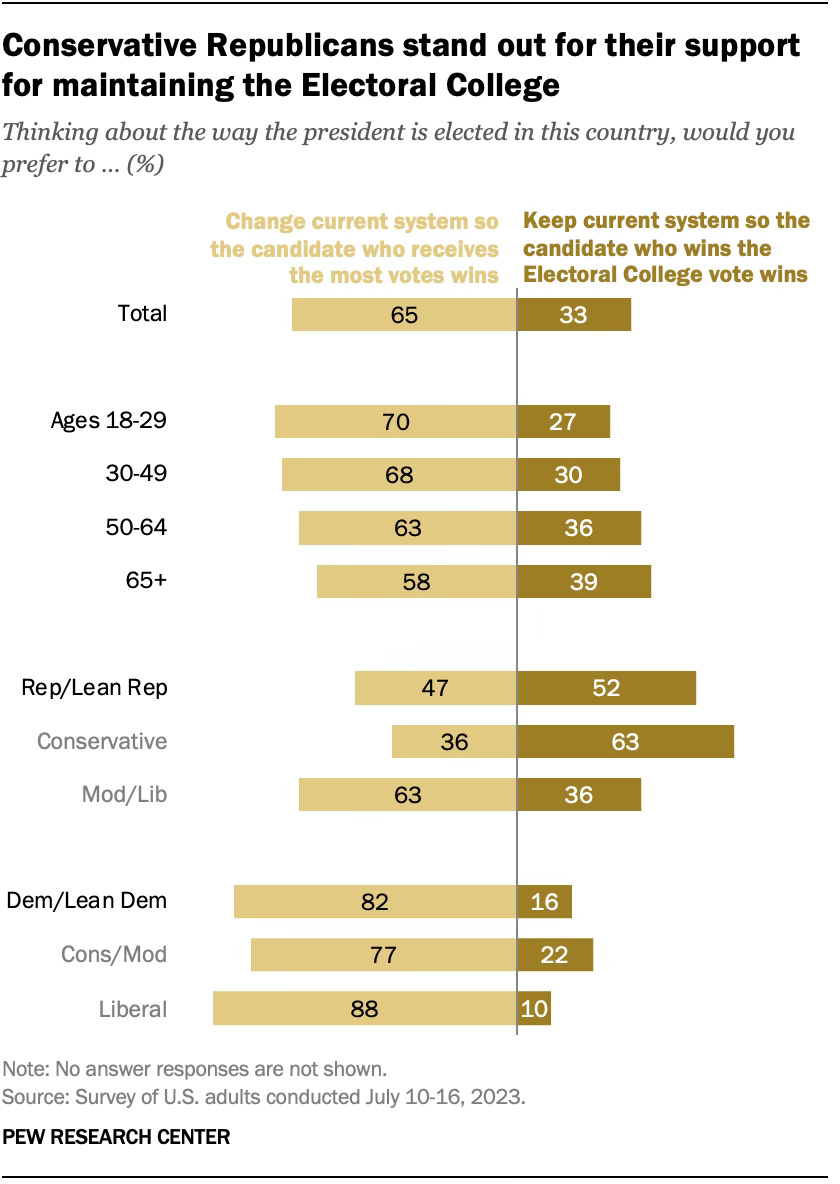

Polling by the Pew Research Center shows that, by a 2 to 1 margin, Americans want to do away with the Electoral College and give voters the power to elect the president directly. Among Democrats, the margin is more than 5 to 1. While liberal Dems polled nearly 9 to 1 against the Electoral College. As you might expect, among conservative Republicans, opinion leans strongly the other way; they favor keeping the Electoral College—63 to 36.

The fact that two recent Republicans wound up in the White House despite losing the popular vote is enough to explain these attitudes. Democrats in this century lost, not only two presidential races to the system, but, as a consequence, they also lost five Supreme Court seats. And thereby, the entire nation lost the guarantee of abortion rights that had been established in 1973 by Roe v Wade. The most recent Court session has left us with a raft additional radical, unsound, and damaging decisions.

The occasional propensity of the Electoral College to upend the choice of the voters is only one reason to reject it.

Even when, as usually happens, the electoral and popular votes concur, the system still skews our elections through a cluster of undemocratic features that not only tilt the playing field but also narrow it, forcing campaigns to focus attention, time, and money on just a few of the fifty states. Despite popular-vote margins in the millions, outcomes in recent close elections have been determined by fewer than 80,000 voters living in a handful of so-called “swing states.” If you happen to live in one of them, you have my congratulations. You have been elevated into a Super Voter, wielding far more influence than I do. Unlike you swing-staters, the vast majority of us live in states that reliably lean decisively red or blue, a fact that mathematically diminishes the power of our individual votes. We are far less likely to influence which candidate gets our state’s electoral votes than you are.

But wait, there’s more. Four years ago, we saw how the existence of a panel of only 538 electors standing between the votes of 154.6 million citizens and the selection of the president creates a target for mischief and malfeasance. Where the Hamilton Elector movement of 2016 had openly aimed at persuading electors who had been duly elected, the fraudulent elector scheme of 2020 worked by subterfuge. The opportunity to secretly purloin the Electoral College proved irresistible to an unscrupulous, defeated president who had spent a lifetime as a serial swindler dancing on the shady edge of legality. Trump and his minions, in their plot to overturn the 2020 results, cooked up a scheme to substitute multiple gangs of imposters for the legitimate electors chosen by the voters. Their attempted “fake elector” fraud is now the subject of both a federal prosecution and five state criminal indictments (in Arizona, Wisconsin, Georgia, Michigan, and Nevada). Eight Trump attorneys are charged in the plot. One has already been disbarred (Bye, Rudy.) Other disbarments are pending (Looking at you, Eastman.) Sadly, none of these cases is on track to be resolved before the November election this year.

So, how did we get here?

How did the United States come to adopt such a cockamamie system in the first place? You’ve likely heard that it reflects a defensive power play by slave-holding Southern states to block the North from outlawing slavery, or that it balanced the power of small states against large. While there’s evidence to support both those explanations, they can account only for the arithmetic of allocating electors to the various states. They say nothing about why we have electors in the first place.

For most of the country’s history, electors have been nothing more than anonymous tokens. Can you name even one of your state’s electors? When MSNBC’s Steve Kornacki goes to the “Big Board” and CNN’s John King goes to the “Magic Wall” to call states on Election Night, they talley electoral votes but ignore the names of the human beings charged with casting those votes. All we expect of our electors is to robotically rubber-stamp the choice of the voters of their respective states.

But the Founders expected something different. Electors were originally charged with using their discernment and knowledge to make an active choice. Hamilton described them as:

“A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass… to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.”

“Complicated investigations”? What could that mean? What were they investigating? And what made it complicated?

The answers lie in the reasons that the Framers declined to put the selection of president into of the hands of voters—reasons that were as much practical as political—reasons that quickly became outdated. Because American presidential campaigns have been so thoroughly baked into our political calendar for more than two centuries, we may have forgotten that we didn’t always have them. When the Constitution was adopted, the U.S. presidential campaign had yet to be invented. We didn’t need them at first. But more than that, we couldn’t stage them.

We didn’t need a campaign at the outset because there was no doubt in anyone’s mind about who first president would be: George Washington, the man who had not only commanded the Continental Army, but also presided over the Constitutional Convention. He was the pre-eminent American. Washington remains the only president ever to receive 100% of both the popular vote and the electoral vote. so, whatever method the Framers devised to fill the office, the first person to hold it was inevitably going to be George Washington.

As for running a national campaign, the country lacked the means and the Framers lacked the will.

What does it take to get famous?

In our time, we’ve seen a telegenic, racist moron with a history of swindles and rapes, a preposterous hairdo, a fondness for long ties, and an obsession with water pressure build a national brand simply based on a reality TV show and a few ghost-written books. But in the late eighteenth century, when the Framers hammered out the Constitution, the barriers to becoming a national celebrity were nearly unscaleable. Imagine the challenge of building name-recognition in an era when people and information could move no faster than the speed of a horse. It would take someone of extraordinary accomplishments to establish a national reputation—someone, for example, who had commanded the army that won American independence.

An even more formidable obstacle to holding a presidential campaign in the time of the Framers was the absence of political parties. Our Founders knew about parties—Whigs and Tories were already long-established in Britain—but they were adamant about not wanting to import the party system to America. No parties meant no nominees. With no nominees, how could voters choose who to vote for?

In a nation that stretched from what is now Maine to Georgia, with no political parties and with no speedy transportation and communication, how could voters ever converge on a candidate? Even in our day, overflowing with communication platforms, candidates struggle to gain name-recognition.

Having deemed it impractical to elect the president by a direct vote of the people, the Convention turned to alternatives. They debated the issue on 22 separate days, holding 30 votes on various methods of choosing the president. They flirted first with one scheme and then another, sometimes circling back to reconsider rejected alternatives—election by the national legislature or by the governors or by state legislatures or by an ad hoc body of electors chosen by state legislatures. Ideas would be voted up one day and voted down the next. Finally after 22 days of getting nowhere and eager to leave town, the delegates punted and assigned the problem of elections to a cleanup squad, a “Committee of Eleven,” tasked with working out proposals for all of the remaining tabled and unfinished details that the Convention had failed to resolve—the thorniest among them, how to select the president.

The Committee of Eleven came back four days later with a two-tiered recommendation—electors plus the Senate. Why two tiers? That’s the topic of the next post.

(TO BE CONTINUED…)

A helpful review of our ridiculous system… thank you, Michael.